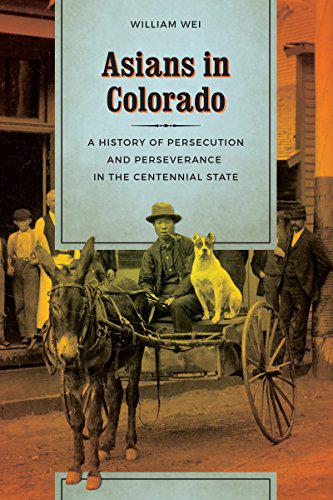

Asians in Colorado

The story of Chinese pioneers in the West

I’ve been working on a manuscript of erasure and found poetry, drawn from archival sources documenting the Anti-Chinese Riots of 1880 in Denver, which contributed to the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. I’m putting this together with my creative partner, Kyle Albasi. We’ll be presenting a walking tour performance of this piece at the Denver Fringe Festival.

One critical text we’ve been combing through for primary sources on the riot has been Professor William Wei’s book, “Asians in Colorado,” which provides a good context for Asian immigration in the Western United States during from early 1800s to present day. In particular, the chapters on the Page Act of 1775 (“Ch. 4 - Importing Chinese Prostitutes, Excluding Chinese Wives”) and the Anti-Chinese Riot of 1880 (“Ch. 5 - The Denver Race Riot and Its Aftermath”) provide an important framework for my writing and creative piece.

I’ve reached out to Professor Wei, who is active on the board of Colorado Asian Pacific United (CAPU) and am eager to visit him at the University of Colorado, Boulder, to consult more on my project.

I’ll be writing more on this book and the advocacy work of CAPU soon.

Review

William Wei’s Asians in Colorado: A Concise History is a foundational text that chronicles the long and often fraught history of Asian immigrants in the state, from the first Chinese prospectors to the diverse communities of the present day. Wei meticulously documents a recurring cycle of welcome and rejection, where Asian immigrants are initially valued for their labor but later targeted as economic and racial scapegoats. The book is organized chronologically, tracing the distinct waves of Chinese, Japanese, and Southeast Asian immigration and the unique challenges each community faced.

Chapters 1-5: The Chinese Experience and the 1880 Riot

The story begins in the mid-19th century with the arrival of Chinese immigrants, drawn to Colorado by the gold rush and opportunities for work on the transcontinental railroad. Wei documents how these pioneers established a foothold in Denver, creating a vibrant Chinatown around Wazee Street, derogatorily known as “Hop Alley.” By 1880, this enclave was home to nearly 500 people, a sanctuary of commerce, culture, and mutual support in a hostile land.

However, as the economy soured, so did public opinion. The Chinese community became a target for white working-class anxieties, fanned by racist politicians and newspapers. This simmering hostility boiled over on October 31, 1880, when a barroom scuffle ignited a full-blown race riot. A mob of nearly 3,000 white residents descended on Chinatown, looting and burning businesses and homes. One man, Look Young, was brutally lynched. Wei uses this event as a crucial turning point, exposing the deep-seated racism that lay beneath the surface of the “Centennial State.” The riot shattered the community, leading to a mass exodus and the passage of further discriminatory laws, culminating in the federal Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which effectively halted Chinese immigration for decades.

Chapters 6-7: The Japanese Arrival and the “Yellow Peril”

With Chinese labor excluded, a new wave of Asian immigrants began to arrive: the Japanese. Initially, they filled similar roles in railroad construction and mining, but soon distinguished themselves in agriculture. Wei highlights their crucial role in developing Colorado’s sugar beet industry, where their expertise in intensive farming turned arid plains into productive fields.

Despite their economic contributions, the Japanese soon faced the same racist “Yellow Peril” rhetoric that had been used against the Chinese. Wei explains how newspapers and labor unions cast them as an unassimilable threat to the American way of life. This sentiment led to discriminatory policies, such as the Alien Land Laws, which were designed to prevent Japanese immigrants from owning the farmland they had made so valuable.

Chapters 8-10: The Trauma of Amache

The book’s most poignant section details the forced incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, over 120,000 people of Japanese descent, most of them American citizens, were forcibly removed from the West Coast.

The Granada Relocation Center, better known as Amache, was established in the desolate plains of southeastern Colorado. Between 1942 and 1945, it imprisoned over 7,300 people. Wei paints a vivid picture of life in the camp—the dust, the guard towers, the loss of freedom—but also the remarkable resilience of the community within. The internees organized schools, a newspaper, and even a successful cooperative farm that produced prize-winning livestock. In a profound display of patriotism, many young men from Amache volunteered for the U.S. Army, serving with distinction in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which became one of the most decorated units in American military history.

Post-War and New Communities

In the final chapters, Wei covers the post-war era, detailing the difficult process of resettlement for Japanese Americans and the arrival of new Asian communities, including Koreans, Filipinos, and, later, refugees from Southeast Asia following the Vietnam War. He analyzes the complexities of the “model minority” myth—a stereotype that simultaneously praises Asian success while obscuring the systemic racism and economic struggles that persist.

By the end of the book, Wei brings the story full circle. He argues that while the faces and origins have changed, the fundamental dynamics of Asian American life in Colorado remain—a continuous struggle for acceptance, identity, and a permanent place in the American West.