China in Ten Words

Tragicomic reflections on China’s transformation through personal and cultural memory

That tragicomic style that is so characteristic of Chinese storytelling. Nostalgia for horrible suffering, made funny with a bashful, resigned forgiveness of the terrifying follies of the Red Guard children - who were throwing rocks at the bourgeoisie, such earnest brutality and virtuous torture, self-policing to cheerful propaganda…stories told by old men now, slumped over stools and slurping noodles in the alleyways of sickly, overgrown cities that have so betrayed them, so made a fool of them. What is there to do except to laugh? Bodies are worth a little bit less during an era of mass death, yet stories are a little more crisply pure, crumbling perspectives more sardonically crystal clear. This book makes me feel closer to my parents. I keep reading it over and over again in English translation, so that I can stumble better over the words in Chinese.

The Architecture of Memory: Ten Words as Historical Framework

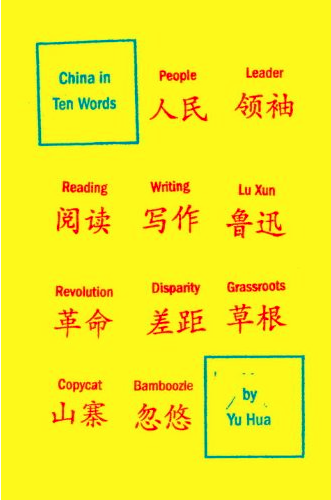

Yu Hua’s choice to structure his memoir around ten words — People, Leader, Reading, Writing, Lu Xun, Revolution, Disparity, Grassroots, Copycat, and Bamboozle — reflects a profound understanding of how language shapes and constrains historical memory. Each word serves as both a linguistic artifact and a historical excavation site, revealing layers of meaning that have accumulated and shifted across China’s tumultuous twentieth century.

This structural approach echoes the Chinese literary tradition of using concrete objects or concepts as organizing principles for larger philosophical reflections, from classical poetry’s use of seasonal imagery to contemporary writers’ employment of everyday objects as metaphors for social transformation. Yu Hua’s ten words function as both personal touchstones and collective symbols, allowing him to navigate between individual experience and national trauma.

The book’s original Chinese title, “十个词汇里的中国” (China in Ten Vocabulary Words), emphasizes the linguistic dimension even more explicitly. Yu Hua is not just recounting history but examining how political upheaval transforms the very words we use to understand our experience. This focus on language as a site of political struggle connects to broader themes in Chinese intellectual history, from the May Fourth Movement’s language reforms to contemporary debates about internet censorship and political discourse.

The Cultural Revolution Generation: Witness and Participant

Yu Hua was born in 1960, making him part of the generation that experienced the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) as children and adolescents. This positioning gives him a unique perspective — old enough to remember the chaos and violence, young enough to have been shaped by it without being fully responsible for it. His memoir captures the particular psychology of this generation, caught between the revolutionary fervor of their youth and the market capitalism of their adulthood.

The Cultural Revolution’s impact on Yu Hua’s generation cannot be overstated. Schools were closed, traditional authority structures collapsed, and children were encouraged to denounce their teachers, parents, and neighbors. The psychological effects of this social upheaval — the normalization of violence, the collapse of trust, the instrumentalization of language for political purposes — permeate Yu Hua’s writing both in this memoir and his fiction.

Yu Hua’s account of his own participation in Revolutionary activities as a child illustrates the complex moral terrain his generation navigates. He describes joining in the persecution of “class enemies” with the thoughtless enthusiasm of childhood, only to recognize later the human cost of these actions. This perspective allows him to examine the Revolution’s violence with both intimacy and critical distance, avoiding both complete condemnation and nostalgic romanticization.

The Tragicomic Tradition: From Lu Xun to Yu Hua

Yu Hua writes in a literary tradition that runs from classical Chinese literature through modern masters like Lu Xun to contemporary writers like Yu Hua. This tradition uses humor not to minimize suffering but to make it bearable and comprehensible, transforming trauma into narrative that can be shared and understood.

Lu Xun, whom Yu Hua discusses extensively in the book, pioneered this approach in modern Chinese literature. Stories like “The True Story of Ah Q” and “Diary of a Madman” use dark humor to expose social hypocrisy and political oppression while maintaining compassion for their flawed protagonists. Yu Hua explicitly positions himself in this tradition, describing how Lu Xun’s work provided a model for writing about Chinese society’s contradictions and absurdities.

The tragicomic mode serves particular functions in Chinese political context. Under conditions of censorship and political repression, humor becomes a way of speaking truth indirectly, allowing writers to critique power while maintaining plausible deniability. The “bashful, resigned forgiveness” you identify reflects this strategy — it allows Yu Hua to acknowledge the horror of recent history while avoiding direct political confrontation.

Language Under Pressure: The Deformation of Meaning

One of the book’s most sophisticated insights concerns how political upheaval transforms language itself. Yu Hua shows how words like “people,” “revolution,” and “reading” have been stretched, inverted, and hollowed out by decades of political manipulation. During the Cultural Revolution, “people” became a weapon used to justify violence against individuals; “revolution” became a cover for personal vendettas; “reading” was reduced to the mechanical recitation of political slogans.

This linguistic analysis connects to broader questions about truth and representation in authoritarian contexts. Yu Hua demonstrates how totalitarian movements don’t just control what people can say but reshape the very categories of thought and expression. His memoir becomes an act of linguistic archaeology, excavating the buried meanings of words that have been corrupted by political use.

The chapter on “Writing” is particularly revealing in this regard. Yu Hua describes how the Cultural Revolution reduced writing to propaganda, eliminating the possibility of authentic expression or genuine communication. His own development as a writer required not just learning new techniques but recovering the possibility of honest language — a process that mirrors China’s broader cultural recovery from the Revolution’s devastation.

The Economics of Trauma: Bodies and Stories

The book repeatedly returns to the paradox that periods of greatest suffering often produce the most memorable narratives, as if extremity strips away everything inessential and reveals fundamental truths about human nature and social organization.

This insight reflects Yu Hua’s background as a fiction writer, particularly his early work in the “avant-garde” movement of the 1980s. Stories like “One Kind of Reality” and “Blood Seller” explored violence and suffering with clinical detachment, using stark, minimalist prose to examine how people respond to extreme circumstances. This aesthetic approach carries over into his memoir, where personal and historical trauma becomes material for artistic transformation.

The relationship between individual suffering and collective memory is central to Yu Hua’s project. He shows how personal experiences of violence, humiliation, and loss become the raw material for broader historical understanding. The “old men slumped over stools and slurping noodles” become repositories of historical knowledge, their stories preserving truths that official histories obscure or deny.

Generational Transmission: The Personal as Political

Yu Hua writes for readers who may not have direct experience of the events he describes but whose families were shaped by them. The book serves as a bridge between generations, translating historical experience into contemporary understanding.

This generational dimension is particularly important for Chinese-American readers, whose parents may have lived through the Cultural Revolution but rarely discuss it directly. Yu Hua’s memoir provides a vocabulary for understanding family histories that may have been transmitted through silence, gesture, and implication rather than explicit narrative. His tragicomic approach makes it possible to acknowledge family trauma without requiring direct confrontation or blame.

The book’s structure around individual words rather than chronological narrative reflects this generational transmission process. Like family stories passed down through fragments and repetition, Yu Hua’s memoir accumulates meaning through the layering of personal anecdotes, historical context, and linguistic analysis. Each word becomes a container for multiple generations of experience and interpretation.

Translation and Cultural Mediation

Allan Barr’s English translation of “China in Ten Words” faces the particular challenge of rendering not just Yu Hua’s prose but the cultural and historical contexts that give his chosen words their resonance. Terms like “grassroots” (草根) and “bamboozle” (忽悠) carry specific connotations in contemporary Chinese that may not translate directly into English. The translator must navigate between literal accuracy and cultural comprehensibility.

This translation challenge mirrors broader questions about how Chinese experience can be understood by international audiences. Yu Hua’s memoir succeeds partly because it provides sufficient context for non-Chinese readers while maintaining the specificity that makes his observations valuable. His approach suggests that cultural translation requires not just linguistic skill but the ability to make foreign experience emotionally and intellectually accessible.

Contemporary Relevance: China’s Ongoing Transformation

Written in the early 2010s, “China in Ten Words” captures China at a particular moment in its post-Mao development — after the economic reforms had transformed daily life but before the current era of increased authoritarianism and international tension. Yu Hua’s observations about inequality, corruption, and social change feel particularly prescient given subsequent developments in Chinese politics and society.

The book’s analysis of “disparity” (差距) anticipated many of the social tensions that have emerged as China’s economic miracle has produced massive inequality. Yu Hua’s observations about the gap between rich and poor, urban and rural, connected and marginalized, provide important context for understanding contemporary Chinese politics and social movements.

Similarly, his discussion of “copycat” (山寨) culture anticipated broader questions about China’s relationship to intellectual property, innovation, and cultural authenticity that have become central to international debates about China’s rise. Yu Hua’s nuanced analysis of how copying can be both creative adaptation and cultural limitation offers insights that remain relevant to contemporary discussions.

The Writer as Cultural Witness

Yu Hua’s memoir positions the writer as a particular kind of cultural witness — someone whose professional attention to language and narrative makes them especially sensitive to the ways political upheaval transforms social reality. His background as a fiction writer gives him tools for understanding how individual stories connect to broader historical patterns, while his experience of censorship and political pressure provides insight into the relationship between power and expression.

This role as cultural witness carries both privileges and responsibilities. Yu Hua’s international recognition gives him a platform to speak about Chinese experience that most of his compatriots lack, but it also creates pressure to represent an entire culture and history. His memoir navigates this tension by focusing on personal experience while acknowledging its broader significance.

The book’s success internationally reflects hunger for authentic Chinese voices that can explain the country’s rapid transformation to global audiences. Yu Hua’s combination of literary skill, historical knowledge, and cultural insight makes him an effective cultural translator, able to make Chinese experience comprehensible without oversimplifying its complexity.

Memory, Forgetting, and Historical Responsibility

Ultimately, “China in Ten Words” is a book about memory — how it’s preserved, transmitted, and transformed across generations. Yu Hua’s memoir serves as both personal recollection and cultural archive, preserving experiences and perspectives that might otherwise be lost as China continues its rapid modernization.

The book’s tragicomic tone reflects a particular approach to historical responsibility. Rather than demanding justice or assigning blame, Yu Hua focuses on understanding and preservation. His goal seems to be ensuring that the experiences of his generation are not forgotten, even as China moves further from its revolutionary past.

This approach to memory and forgetting has broader implications for how societies deal with historical trauma. Yu Hua’s memoir suggests that healing requires not just acknowledgment of past suffering but the transformation of that suffering into narrative that can be shared and understood. The tragicomic mode makes this transformation possible, allowing readers to engage with difficult history without being overwhelmed by its horror.

A Bridge Across Time and Culture

“China in Ten Words” succeeds as both literary memoir and cultural document because it provides multiple entry points for different kinds of readers. For those with direct experience of the events Yu Hua describes, it offers validation and articulation of shared experience. For those learning about Chinese history and culture, it provides accessible introduction to complex topics. For Chinese-Americans and other diaspora readers, it offers tools for understanding family histories and cultural inheritance.

Your experience of reading the book repeatedly, using it as a bridge to better understand Chinese language and culture, reflects this multifaceted appeal. Yu Hua has created a work that functions simultaneously as personal memoir, historical document, linguistic analysis, and cultural bridge — a rare achievement that helps explain the book’s enduring impact and relevance.