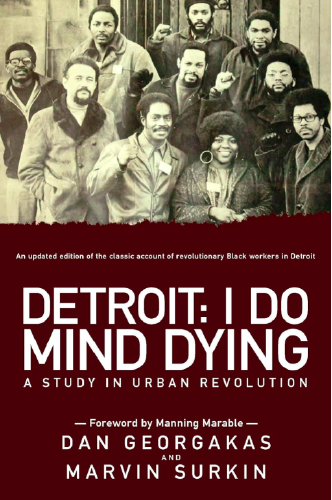

Detroit I Do Mind Dying

History of revolutionary Black workers organizing in Detroit’s auto industry

This book should be a mandatory textbook for organizers. Incredibly well-researched history and personal accounts of auto workers organizing in Detroit during the 1960s and 1970s at the League of Revolutionary Black Workers and DRUM (Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement) — highlighting the intersections of race, gender, class, and conflicting ideologies. The final two chapters on our current state of fighting against transnational capital provide a good framework for today’s movements, informed by the successes and failures in Detroit.

A Revolutionary Model for Labor Organizing

Georgakas and co-author Marvin Surkin document one of the most significant yet underexamined chapters in American labor history: the rise of revolutionary Black worker organizations that challenged both corporate power and the conservative white leadership of established unions. The League of Revolutionary Black Workers emerged in the late 1960s as Black workers, who comprised nearly 60% of Detroit’s auto workforce, found themselves systematically excluded from union leadership and subjected to the most dangerous, lowest-paying jobs on the assembly line.

What makes this book essential reading is how it demonstrates the limitations of traditional labor organizing that fails to address racial oppression. The authors show how DRUM and similar organizations like FRUM (Ford Revolutionary Union Movement) and ELRUM (Eldon Avenue Revolutionary Union Movement) developed new models of organizing that explicitly connected workplace exploitation to broader systems of racial and economic oppression.

Intersectional Analysis Before the Term Existed

Long before “intersectionality” became academic parlance, these Detroit organizers were practicing it. The book reveals how Black women workers faced triple oppression — as workers, as Black people, and as women — and how the revolutionary organizations attempted (with varying degrees of success) to address gender dynamics within their own ranks. The tension between revolutionary rhetoric and patriarchal practices within the movement provides sobering lessons about the challenges of building truly liberatory organizations.

The authors don’t romanticize these movements. They honestly examine internal conflicts, ideological disputes between nationalist and Marxist factions, and the ways that ego and personality conflicts sometimes undermined collective action. This unflinching analysis makes the book more valuable, not less — it shows that revolutionary organizing is messy, contradictory work that requires constant self-reflection and course correction.

Tactical Innovation and Strategic Vision

One of the book’s most valuable contributions is its detailed examination of the tactical innovations developed by these organizations. From wildcat strikes timed to disrupt production quotas, to the use of underground newspapers and community organizing, to the development of independent political candidates, the Detroit revolutionaries pioneered approaches that connected workplace organizing to community power-building.

The League’s vision extended far beyond better wages and working conditions. They understood that the auto industry’s exploitation of Black workers was connected to broader patterns of urban disinvestment, police violence, and educational neglect. Their organizing reflected this systemic analysis, linking factory struggles to housing campaigns, anti-police brutality work, and efforts to democratize public education.

Contemporary Relevance

The book’s final chapters, examining the legacy of these movements in the context of globalized capitalism, feel remarkably prescient. Written decades before the 2008 financial crisis and Detroit’s bankruptcy, Georgakas and Surkin anticipated how deindustrialization would devastate working-class communities of color. Their analysis of how transnational capital mobility undermines local organizing efforts speaks directly to contemporary challenges facing labor and community organizers.

Today’s movements for economic justice — from Fight for $15 to the Amazon Labor Union to racial justice organizing — can learn crucial lessons from the Detroit experience. The book demonstrates both the possibilities and limitations of revolutionary organizing within capitalist structures, and the absolute necessity of centering racial justice in any serious challenge to economic inequality.

A Living Document for Organizers

This isn’t just historical documentation — it’s a strategic manual. The authors’ backgrounds as participants in and chroniclers of these movements gives the book an insider’s understanding of organizational dynamics, strategic decision-making, and the personal costs of revolutionary commitment. The extensive use of first-person accounts and internal documents makes the reader feel present in strategy meetings, on picket lines, and in the moments of triumph and defeat that define any serious organizing campaign.

For contemporary organizers grappling with questions of multi-racial coalition building, the relationship between reform and revolution, and how to maintain radical vision while achieving concrete gains, “Detroit I Do Mind Dying” provides both inspiration and hard-won wisdom. It reminds us that the most powerful organizing happens when people connect their immediate struggles to broader visions of social transformation — and that such organizing, while difficult and often dangerous, remains absolutely essential.