MexiCable

Cablecar for the people.

During a recent company offsite with AidKit, I was lucky to have the chance to ride on the MexiCable lines on the outskirts of Mexico City. Consisting of two public transport lines by cable car, each running approximately 30-45 minutes each way, this inexpensive gondola system was built to allow residents in outer city slums to access healthcare, social services, and jobs in wealthier parts of the city.

The MexiCable is an innovative urban transportation system located in the impoverished municipality of Ecatepec in CDMX. It was inaugurated on October 4, 2016, and stands as a prime example of how urban cable cars can be integrated into public transport networks to enhance connectivity and improve living conditions in marginalized areas. This system was inspired by successful implementations in other cities, notably the MetroCable in Medellín, Colombia, which was launched to serve similar social and economic purposes by connecting remote hillside communities with the city’s metro stations.

Context and Impact

Ecatepec is characterized by its challenging topography and high-density population, factors that have historically limited residents’ access to efficient public transportation. The MexiCable was designed to address these barriers. Each line stretching over 4.9 kilometers and comprising fourteen stations, this cable car system reduces what was once an 4 hour journey down to just 17 minutes. This transformation is crucial in a region where daily commutes are long and cumbersome, impacting the residents’ quality of life and access to economic opportunities.

The introduction of the MexiCable has been transformative for the community. It not only provides a rapid, reliable, and secure mode of transport but also significantly improves the safety of commuters who previously relied on less secure forms of public transport. The cable cars are equipped with cameras and operate in an environment that reduces the risk of petty theft and assaults prevalent in other public transportation options like minibuses. Currently, the MexiCable serves approximately 18,000 passengers per day.

One of the notable benefits of the MexiCable is its environmental impact. As a fully electric system, it contributes to the reduction of carbon emissions by offering an alternative to fossil-fuel-dependent road vehicles. This is especially important in urban areas like Mexico City and its surrounding regions, where air quality is a persistent public health concern. The reduced commute times also mean less time vehicles spend idling in traffic, which further decreases the urban carbon footprint.

Medellin MetroCable

Mexicable borrowed its model of urban planning from the Medellín MetroCable, one of the first systems to demonstrate the viability of cable cars as an integral part of an urban public transport network. This MetroCable system highlighted the potential for such systems to bridge the gaps left by more traditional forms of transportation, especially in geographically challenging areas, to benefit underserved residents.

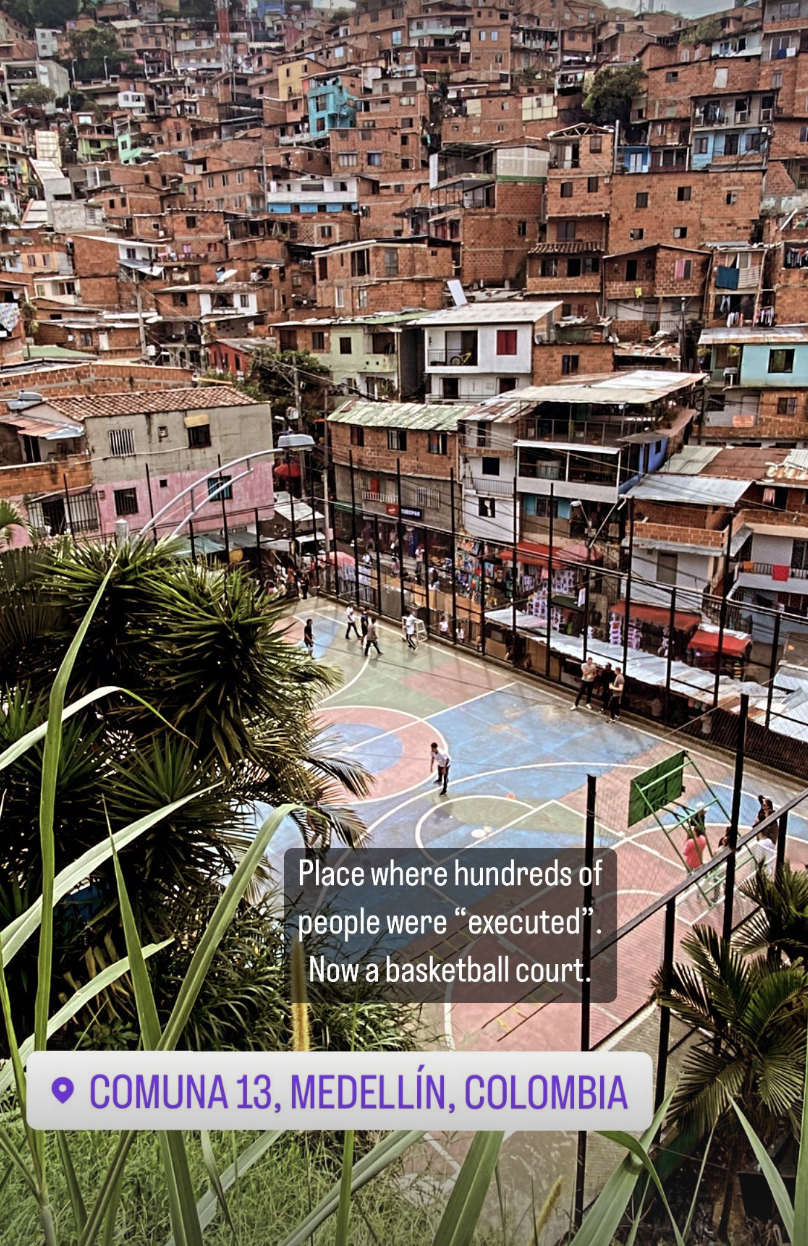

Communa 13, also known as San Javier, is one of the most densely populated districts of Medellín, Colombia, and has a tumultuous history marked by violence and social strife. During the 1980s and 1990s, it was considered one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in Medellín due to the heavy presence of drug gangs, guerrilla groups, and paramilitary forces. The area was notorious for homicides and forced displacements.

The transformation of Communa 13 began in the early 2000s as part of a broader urban renewal strategy implemented by the city of Medellín. This strategy included integrating marginalized neighborhoods into the city’s economic and social fabric through innovative public transport solutions and community projects.

The Medellin MetroCable, a cable car system built in 2004, was part of a larger project to improve accessibility to Medellín’s hilly and previously isolated neighborhoods. The MetroCable connected Communa 13 to the city’s metro network, drastically reducing commute times and integrating the community with the broader city. This accessibility helped to boost local economies and allowed residents easier access to work and educational opportunities.

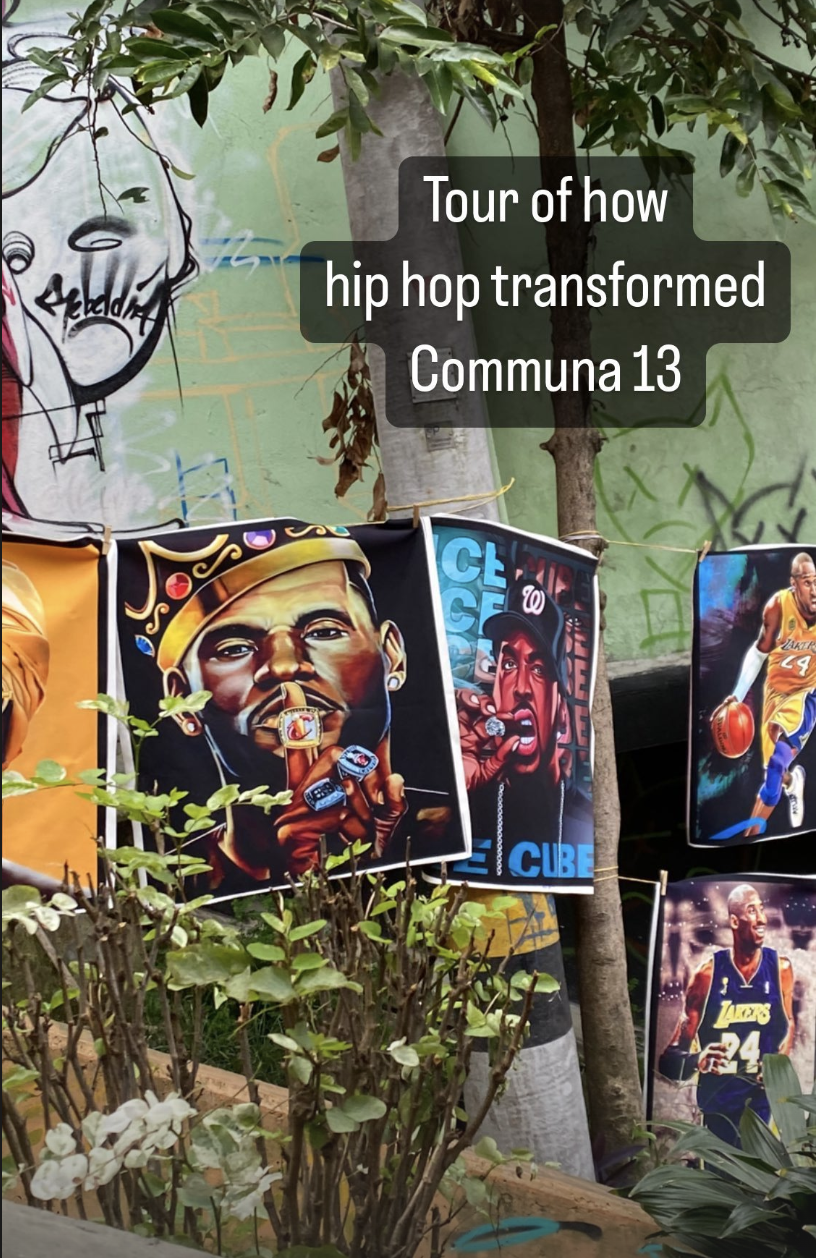

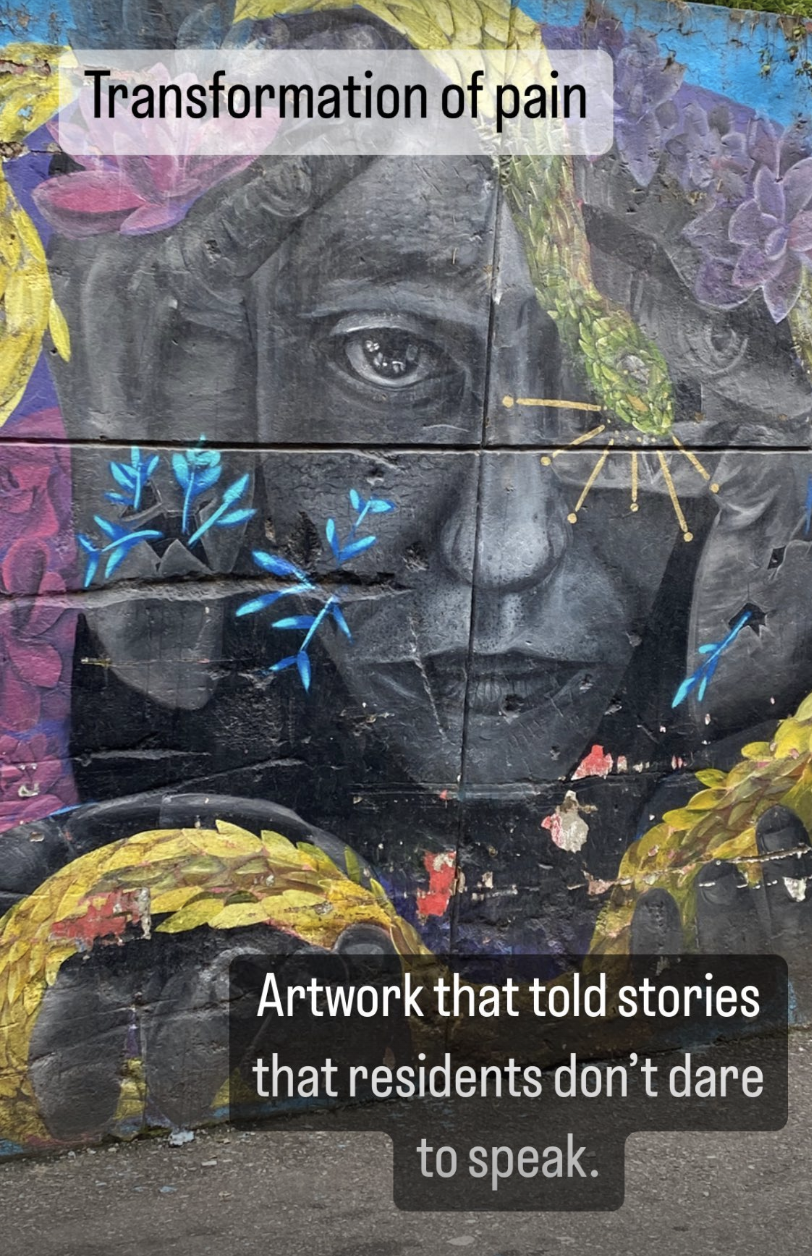

Alongside infrastructure improvements, the transformation of Communa 13 was significantly supported by investments in public art and community engagement initiatives. The neighborhood walls turned into canvases for local artists, with murals and graffiti depicting stories of resilience, peace, and community life. This public art movement not only beautified the area but also attracted tourists, further stimulating the local economy and changing the neighborhood’s reputation.

These interventions, particularly the public art projects, played a crucial role in altering the social fabric of Communa 13. They provided a platform for residents to express their identities and experiences, fostering a sense of community pride and ownership. Educational programs and community centers sprung up, focusing on youth engagement and violence prevention, contributing to a significant drop in crime rates over the years, and greater safety and prosperity in the community.

The success of the MetroCable in Medellin and MexiCable in CDMX provide a blueprint for other cities facing similar challenges, offering a model for how cities can innovatively tackle the dual challenges of urban transport and socio-economic development.

A few years ago, when there were talks about shutting down the L-line connecting Brooklyn to Manhattan, someone floated the idea of a East River Skyway – a beautiful project that I hope to see one day.