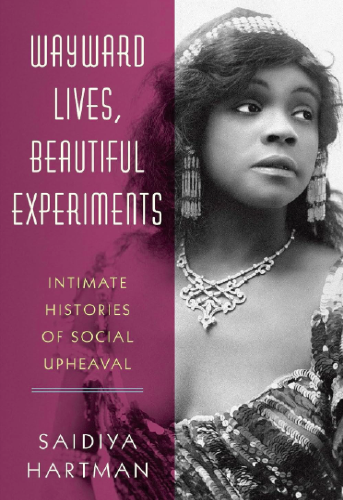

Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments

Intimate histories of social upheaval and Black women’s resistance

Breathtakingly beautiful prose, composed from painstakingly researched historical artifacts. Such an important story told here about the ways in which the Loitering for Prostitution laws have always been used to profile black women for simply being visible on the street; to control bodies, criminalize to compel forced labor, and limit economic options for the city’s most vulnerable and most intrepid women. It’s past time we repealed this law in NY.

The stories of lesbians, transgender and cross-dressing women, women involved in sex trades or profiles as such, span the range of dire antebellum poverty and torturous imprisonment for the crime of pregnancy out of wedlock, to the glamorous madames of Harlem who consorted with the city’s famous entertainers, artists and intellectuals, politicians.

No understanding of race and sex work in America is complete without reading about the ways in which Black women’s bodies were treated under slavery, and the ways Black families have long been broken down by the structural violence of racism and poverty, then maligned as being immoral. Or how criminalization was used to force Black “wayward women” into domestic work, after the Emancipation Proclamation supposedly ended the institution of slavery in the US.

Important book I will be reading over and over again, for reference.

Review

Saidiya Hartman’s “Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments” is a groundbreaking work of history and imagination, reconstructing the lives of young Black women in New York, Philadelphia, and beyond at the turn of the twentieth century. Hartman uses “critical fabulation”—a blend of archival research and narrative invention—to give voice to women whose stories were often erased or distorted by official records.

Hartman’s central argument is that the so-called “wayward” lives of Black women—those who defied social norms, lived outside the bounds of marriage, or engaged in sex work—were not simply deviant, but radical experiments in freedom. She writes: “The chorus of young women who improvised new ways of living, loving, and being, who refused to labor like slaves or to be bound by the law, were the true radicals of the twentieth century.”

The book is rich with facts and statistics: by 1910, more than 90% of Black women in northern cities worked as domestic servants, yet many resisted this fate, seeking autonomy in boarding houses, rent parties, and same-sex relationships. Hartman details how laws like “loitering for prostitution” and “incorrigibility” were used to police Black women’s bodies—between 1910 and 1930, thousands were arrested in New York alone for such “crimes.”

Hartman’s prose is both poetic and incisive: “The crime was existence itself, the offense was visibility.” She shows how Black women’s sexuality was pathologized and criminalized, and how the state sought to control their labor and mobility. Yet, she also foregrounds resistance—through love, kinship, and creative survival. “Waywardness is a practice of freedom, a refusal.”

She writes about the “afterlife of slavery”—the persistence of racial and gendered violence after emancipation—and the idea that everyday acts of defiance can be revolutionary. Hartman’s work challenges the boundaries of history, biography, and theory, insisting on the value of lives lived at the margins.

Hartman’s blend of rigorous research and imaginative empathy is deeply impactful for me in terms of thinking about what is possible in the literary craft of history-writing as prose and poetry.